|

|||||

|

||||||||||

| Europe & Scandinavia | ||||||||||

|

A Ghost of

Russia's Past Boris Leonidovich Pasternak must be singing in his grave. Once forced to decline the Nobel Prize and banished to rural exile, Pasternak's reputation has been redeemed. Today he is an icon, a revered hero of the populace and a maligned traitor of the state. Now the Russian cognoscenti recite his poems by heart and tourists are carted off to his dacha, or cottage, for a taste of his courage.

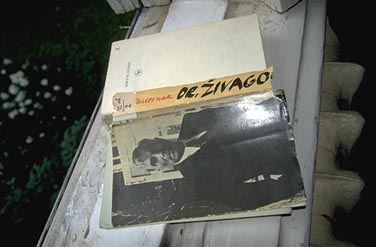

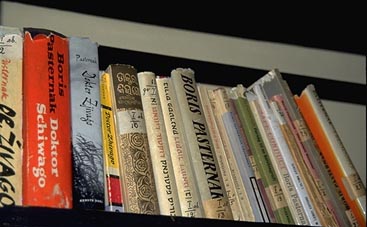

En route to Peredelkino, the scattering of dachas range from humble frame cottages to imposing brick or stucco edifices with pools. A cracked sign marks the way to Pasternak's domain. Following a quiet tree-lined path, we arrive at a Victorian-style frame house to find a slight gentleman in a tweed jacket waiting on the step. Lev Parmas, scholar-in-residence of Pasternak's works, does not speak a word of English. Yet his tour, translated by our guide, is fascinating, if only for the emotion in his voice, his eloquent body language, and of course, the house itself. The Pasternak story is well known. The government refused to allow the publication of Dr. Zhivago, his only book of prose, because of its "subjective" anti-revolutionary views. The manuscript was smuggled out of the country (supposedly without the author's knowledge) and published in Italy. Consequently, the Union of Writers ousted him.

Ironically, Pasternak won the 1958 Nobel Prize ""for his important achievement both in contemporary lyrical poetry and in the field of the great Russian epic tradition." Infuriated that he mocked Soviet principles by accepting the prize, the Kremlin forced him to refuse it. Pasternak was then exiled to the Peredelkino dacha and was forbidden to write or translate works. His wife was deprived of her pension, and he lived under the eye of the KGB until he died of cancer in 1960. Pasternak aroused worldwide sympathy. "Am I a gangster or a murderer? Of what crime do I stand condemned? I made the whole world weep at the beauty of my land."

His poetry became a hushed mantra for the people. Perched on the top step with the formality of a Shakespearean actor, Parmas recites, in Russian, Pasternak's poetry: "When everything ends, only the earth and the grass continue to breathe." He recounts Pasternak's legend while leading us through the house. "Pasternak settled here in 1939. Cool autumn. Russian winter. No heat. Just a stove. His character, Zhivago, takes care of stove, too." The showpiece of the main floor is the dining room. The furnishings are simple: wood table, unadorned samovar, 1950's television. But the walls bear Pasternak's legacy. The only photograph in existence of Pasternak being honored for his Nobel Prize shows him being toasted in this very room. There are also an assortment of pictures and paintings by Pasternak's father, who was an illustrator for Leo Tolstoy. "Pasternak foresaw things. He convinced his parents and younger sister to leave Russia for Germany after the revolution. Then in 1938 to flee to England - they were Jewish.

Parmas steps back, and with palpable feeling, recites the poem I'm all by myself. We follow him in silence upstairs to the writing studio, a long room with wide- windowed end walls, a sleeping alcove at one end, a study at the other. "This room was Pasternak's happiness. Here he was Dr. Zhivago at his window on the world." Indeed, windows transcended their physical meaning and figured prominently in Dr. Zhivago's thoughts. "Looking out the window one August morning, Pasternak saw his own his death. This inspired his poem "written" by Yuri Zhivago." Raising hand to heart, Parmas recites it in an audible whisper. "Pasternak died August 6."

Parma's words escape me, but his emotion is heartfelt. Peering out the window at the leafy trees and flowering shrubs, I feel my eyes brimming with tears. I turn to see an old woman who has followed behind us - a housekeeper or spy - acknowledge my feelings with a nod. Sitting on his chair, touching his desk, I wonder: Could I write a Dr. Zhivago here? " After his death, what then?" I ask. No answer. It seems literati and guides still tread a fine line. But I know. Pasternak's family lived here until November 1984 when they were evicted after a court battle with the Writers' Union in spite of the family's desire to preserve it as a museum. At the nearby cemetery where Pasternak is buried, a woman sells plastic posies to lay at his grave: US $15 a bunch. I lay a stone, in the Jewish custom. Pasternak, the ghost of Russia's past who was denied a burial ceremony, has the biggest headstone and the biggest private plot. As we drive away, we see the woman collect our posies and stones. Getting There: Peredelkino is 25 km west of Moscow. Consult your hotel concierge for directions. Admission: $5. Our guide charged $60 for a half-day excursion including transportation. |

||||||||||

|

Register Free at travelteriffic.com Back to HOME PAGE Copyright © 2000 travelterrific inc. All rights reserved. Privacy Statement

|