|

|||||

|

||||||

| Literary | ||||||

|

Avoiding

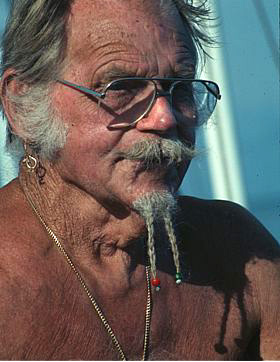

the Midnight Buffet He was "Offshore Eddie" to the Caribbean's windjammer fleet and hundreds of passengers who sailed with him. Also, sometimes, "Fast Eddie." Only the very few - skippers, paymasters - knew his real name: Anagar Johannes Bloom Orevik. To me, unimaginatively, he was "The Old Man of the Sea." He, reputedly, was one of only six sailmakers-by-hand of canvas left in the world. But his business card read differently. Created by a jocular passenger, it proclaimed "Sailmaker and Marriage Counselor." That combination resulted from a recent tack in Eddie's life. For many years he was aboard the Amazing Grace, the supply ship for Windjammer Barefoot Cruises. He picked up torn sails from six windjammers throughout the islands, repaired them, and returned them weeks later. Some years ago, Jill was a passenger aboard the Amazing Grace. She was smitten with Eddie, a not uncommon state with women. Shortly afterwards she returned for a second cruise, with her mother. It was on that trip that Eddie, then 80, and Jill half his age, were married on a tug in international waters. They had a double honeymoon, half on a windjammer, half criss-crossing America in an 18-wheeler. Jill was a trucker. There is no knowing whether Jill was Eddie's first or sixth legal wife. But if his marital record had been wobbly, it was nothing compared with his life history. He ran away from his Norwegian home when 14, drifted all over the world - Africa, Russia, South America. He was an "illegal" in the U.S. before that term was current. He was, for one spell, an "illegal businessman," handling a cockleshell coaster called Skol along the New England coast. It was then he gained his nickname. Sailing somewhere between Newfoundland and Long Island Sound (with Eddie's stories it was necessary to allow many degrees of latitude), he was trapped for two weeks by calm, fog, pack ice. The aft cabin had to be burned to keep Eddie warm, if you believe Eddie. Still, there was someone to worry about him, an only relative in the United States, an uncle. After not hearing from Eddie for some days, the uncle started calling the Coastguard. It reported him safe, offshore. Other calls brought the same report and location: "Offshore." By the time the ice had loosened, the cargo reached a port, Eddie, unknowingly, had a new moniker. Onshore, red tape finally caught up with Eddie. World War II was over. The U.S. had gone formal. Eddie was hauled before a Brooklyn court. Although having come in and out of the States dozens of times, he had never registered as an immigrant. Luckily, the judge was a woman. She quickly came under the spell of Eddie's twinkling eye. She told him what he should do. He must take the train to Montreal, return to the U.S. border, and there apply for immigration. Some think she accompanied him to make sure he did things right by her. Eddie says it was five years later that he became an American. He is precise about dates. Fifty years after starting, he gave up smoking. Jack Daniel's was relinquished in 1987: "took me ashore with a bleeding ulcer, had to give up something." This meant going ashore less and less: "didn't have any bars to go to."

Yet he wasn't as precise about Jill when I was aboard the Grace on another trip. I found him still working on the sails every day, but he had slowed, was more subdued. She was not aboard, she was never mentioned. It was in 1951 that Mike Burke, founder of Windjammer Barefoot Cruises, invited Eddie aboard. Ever since he has been on the sailing ships that once were the luxurious yachts of millionaires like Onassis, Vanderbilt and Barbara Hutton, and the Amazing Grace. Once, Eddie saved one of those yachts, the Yankee Clipper, in a hurricane by advising the anchor chain be coiled around two palm trees. It was not for exploits like these, however, or his marriages, that Eddie became something of a mascot of the fleet. It was more because of his age and his becoming looks. For he was built like a thong. He only pulled a shirt over his bronzed octogenarian body for meals, so passengers (and should we allow, particularly women passengers) could admire his healthiness as, in only a pair of shorts, he put grommets into sails, handled a marlin spike, repaired rips on deck, mornings and afternoons. Age had determined that he now wear steel-rimmed glasses for this work. His hair had also thinned. But not his salt- and-pepper beard. This dangled in two ends. They had been prettily beaded in the West Indian fashion by " the girls" - the Caribbean kitchen help on the Grace. The beads complemented Eddie's only other adornment, a teener's gold ring in one ear. It was because of people like Eddie that I have always preferred small ships. There have been necessary exceptions. I sailed on the second peacetime voyage of the original Queen Elizabeth, in 1946. The Duke and Duchess of Windsor were aboard. Molotov, the obdurate Soviet foreign minister who had a deadly "cocktail" named after him, was on the first. I used to amuse myself wondering what a meeting between them would have been like. I only saw the Windsors once. On Nov.11 the British class barrier, more lasting than any Berlin Wall, came down for a Remembrance Day service in the first class lounge. It was due to start at 10.30 so the Last Post could be played at 11. The captain was to escort the Windsors to their front row seats. At 10.55 they still hadn't arrived. For 25 minutes, the congregation, not all monarchist, had been turning their heads. No announcements. No music. Just waiting. With their final arrival, the service began - backwards. The Last Post was blown, then the Reveille, then the service began from the beginning. It was the Duke's turn to swivel his head. All the time. Backwards. Sideways. Downwards. He obviously had DTs. Molotov would have simply looked ahead, glum. Old Stoneface would have been punctual. In tourist class, I was a nonentity on that ship. Not only did I not eat at the Captain's Table, I never saw it. I was to make up for it on another Cunarder. Aboard the Cunard Countess, many decades later, down the Mexican coast, M and I were directed to sit with the captain the first night at sea. I found this odd. Modern captains, I knew, were increasingly P.R. men for the line - with limp hands from shaking thousands of passengers' hands, fixing smiles for the photographers - but there was only a Captain's Table once, at most twice, a voyage. But this was different. This captain had four couples with him the first night, and the same couples every night of the trip. No one explained why. Half way through the week, we decided, it must be because he was shy. By the end of what became a numbing experience, I was telling him I knew more about him than my own children. There were no Captain's Nights on the Amazing Grace. Nor a casino, cruise director, organized shore excursions, which suited me fine. Nor a wine list, printed menus, midnight buffets, set seating arrangements. Instead, passengers squeezed into large circular booths. The West Indian waiters served reasonable wine from a pitcher and hefty helpings of food from the ends of each table. Passengers passed plates around. The bar was a complete circle. The young Scottish barman climbed over it to serve. So did his assistant (and also his girl friend), whom he had smuggled aboard. The last night of a three-week voyage, with 16 ports-of-call between the Bahamas and Trinidad, was the only formal night, declared by the captain. That meant, he said, he would be changing his shirt. We never did see him in anything but shorts. He was all of 25 and Welsh. Each morning, he gave a five-minute chat, which mainly consisted of warning whether the local taxi-drivers were "pirates" or not.

The Grace was meant to be doughty, not luxurious. It had been built for the Commissioners of Scottish Lighthouses to make surveys in the heavy seas around the Hebrides. It was a tough little vessel of warm wood and polished brass. Apart from provisioning the windjammers in its second life, it carried up to 80 passengers and some cargo. Some of the ports-of-call were as minor as the ship in the realm of cruising. So we were not surprised one morning to find ourselves anchored off flat Inagua, the first Bahamian island to be reached from the Dominican Republic. What was extraordinary was that we were to have an organized trip. Transportation, we soon discovered, was that bunch of trucks we could see at the end of a jetty, with forms for seating. We set off for Mathew Town, the only village. As we passed what seemed to be the general store, two men waved at us. How amiable, we thought. We went on to look down on the island from a lighthouse, headed back, got more waves (this time from three men), passed the salt pans which supply the States with a quarter million tons annually, reached a beach for swimming and a picnic lunch. It was a languorous time. That is, until, mid-afternoon, a twin-engined plane started buzzing us. On the drive back, it swooped low over the trucks. While awaiting the ship's tender, it continued its dives. That was before we heard rifle fire. Only next day, picking up a paper in Nassau, did I catch the word " breakout" in a headline. Three drug traffickers had escaped the Inagua prison. Their cache, it was believed, had been hidden by a girl friend in the general store. Obviously, when they returned for it they hadn't expected to be interrupted by "tourists." The manhunt had involved a plane. At dusk the evening before (about the time we upped anchor), the score was 2-1. One man had been picked up after warning rifle shots, a couple were still on the lam. In small ships experiences soon become common currency. So, at dinner aboard the Grace one night, we heard how three Albertans, two men and a woman, had almost met disaster that afternoon when caught by a flash flood on a Dominica waterfall. The guys, previously, had struck us as jocks. The evidence: how busy they kept Scotty at the bar, ordering Buds. But this night - and for the remainder of the trip - they were different: born-again ponderers. At another meal, breakfast, there was more affecting news: a passenger who had passed us our plate the night before, had died. He was a Seattle doctor, traveling with his wife. He had left dinner to be stricken in his cabin. We learned he knew his heart condition meant his months were numbered. So he and his wife spent their remaining time together, doing what they liked best, roaming the oceans in small ships. The Grace, in death, did him proud. There being no other doctor aboard, the captain and a female passenger who was a police office signed the death certificate. The ship was diverted to Tortola, chosen because the captain had friends there who could help the widow. The body was taken ashore. The ship continued on its course. Passengers' ages on the Grace balanced the youth of the crew. So death was a wild card. When death came, the hymn Amazing Grace (written by a reformed slave ship captain) might have comforted some. We all hoped so for the doctor, that he had heard it the evening before his sudden, but expected, death when, as usual, it was played as the ship left port. There were three versions, on a tape, on bagpipes by a crew ember, and occasionally, equally plaintively, on a saxophone by a company official, visiting from Miami. Crowded into booths, different combination at every meal, we soon got to know each other. There was the blind man who ran a Florida business selling two of the world's beauties - orchids and tropical fish. Another passenger, a Chicago tax collector, read him some of the verse he had written. Two sisters used the ship as a rendezvous - one lived in British Columbia, the other in England. "Punchie", an American woman, loathed large cruise liners, so regularly chose the Grace (on which she played cards interminably.) Another American was the daughter of one senator, married to another. There were high steel construction workers, a Nova Scotia innkeeper who video'd everything, a German, a Cuban, a Czech. A regular sight in port was to see some crew member given a touching farewell. Most only saw their families for a few hours every three weeks. They would go off to villages in the hills or narrow streets in an island capital bearing gifts brought from Freeport or Miami. Then at dusk, at dockside, a wife and baby, sometimes with a whole gaggle, often an entire extended family, would wave and wave until the ship had passed beyond the buoyed exit channel. Yet only Eddie, of those Grace crew members, is as memorable as Fridt, another sailmaker, on another ship, but also in the Caribbean. Fridt was no ordinary sailor. He had been summoned from Holland by Michael Krafft, a Swedish millionaire yachtsman with a love of old ships. Krafft was building the Star Flyer, the world's only true replica of a clipper ship. Would Fridt, known for his sailmaking and ability to create beautiful model ships in bottles, come aboard? Fridt made a deal: for half a day he would mend sails, for the other half he would be the ship's "entertainment", building miniatures of the Star Flyer. I met him cutting one out, painting the hull, rigging the tiny ship. He did this every week in the ship's library. Then on the Thursday evening of each week's sailing, with nearly every passenger in attendance, he would pull the threads to raise the rigging inside the bottle On Friday night came the finale. The finished ship-in-a-bottle was auctioned. On my sailing it sold for $650 to a retired locomotive engineer, who had hovered over Fridt through the week. That was average, Fridt said, although once he had got $1,050. The Star Flyer sailed out of St. Maarten in winter, sometimes put all its 15 sails up in the Mediterranean during summer cruises. It was on one of these that Fridt jumped ship. He chose Monaco. How do I know? Because, a couple of years after being on the Star Flyer, I was in a ship bottle museum in a small Dutch town beside the Ijsselmeer. I had seen the collection and was about to leave when I asked the owner whether he happened to know a model-maker called Fridt who had….. I didn't need to name the ship he had been on. "He's upstairs, carving," was the reply. With all sails set in a good Caribbean breeze, the Star Flyer only once made 10 knots. This suggested that the 19th century was dosed with hype too, for great excitement surrounded the "races" between clippers bringing tea from China, grain from Australia - at their end, because there was no radio to give ships' positions, no satellite TV for replays of notable seamanship. Retrospection has romanticized the 100-day voyages aboard clippers when, as in war, life aboard was nine-tenths boredom. At least that was the view of Captain Paul Summerlund. I had sought him out in a seniors' home at Mariehamm, in the Aland Islands. A seed bed for sailors, halfway between Sweden and Finland, it was on my visit the home of many of the 250 "Cape Horners" still living - men who had sailed round that dreaded geographical poignard. This select breed gathered monthly at a maritime museum, which had as its appropriate neighbor the Pommern, a moored, preserved clipper ship. One among their company was even more select: Paul Summerland. He was a " Cape Albatross," the title given to a clipper captain who had rounded the Horn. He was the only one left, brought down in his wheelchair to mumble about those sometimes boring days, in defiance of photos around the museum walls showing decks awash, crews trying to reef sails in berserk winds. It was as if this old man's life (since ended) had been made up entirely of halcyon days, with his ship meeting 10 knots without a stir from the crew and only the slightest adjustment to helm or line. Whereas, he had left sail for steam by World War II, was crossing the Atlantic, had been sunk, been made prisoner. Mariehamm is a clean, freshly painted, bilingual town surrounded by rocky, clear water coves. Not unlike Camden, Maine (except for the language, which there is unadulterated Yankee.) That's where M and I boarded the Stephen Tabor, oldest wooden sailing ship registered by the U.S. Coastguard. Camden is the capital of holiday windjammer cruises, that pleasure of the adventurous, a week from hell for those who cringe at confinement. The Stephen Tabor was especially testing. There were 26 of us. That included four passengers who had laid out several hundred dollars to sleep on benches around a large wood stove. They were awakened at 5.30 each morning by the captain's wife who, with a girl to help, was there to bake bread for the day and prepare breakfast. Captain Barnes and his wife Ellen (the cook, although she also held a master's ticket), a certified mate, the female pot-washer and an apprenticed youth made up the crew. Again the passengers proved an advantage of small ships. Among them: an English girl holidaying in the States who, joining the ship at the last moment, deserved her toasty bench; a psychologist who openly made suggestive overtures to a not particularly sexually attractive woman traveling with her husband and two children; an Oregon mother who had joined her daughter, at university in New England; a band of hefty martini drinkers who should have been in a golf club. None could provide as intriguing a history as the Barnes. They had, into their late thirties, been teachers of theatre and English at a North Carolina college. They had, just like us, come to Maine to take a windjammer vacation. To say they were hooked was an understatement. Before they left Camden, they were obsessed to the point that they had left their names with ship brokers, had decided to learn seamanship, one day own their own 'jammer. Back in the South, they started correspondence courses, made weekend visits to nearby harbors, pestered old salts, enquired, sailed, learned. They were determined to give up teaching, start a new life. It would take several years. It was an awry plan. Time overwhelmed them. A phone call informed them of a ship for sale, terrible shape, good price, they better jump. They did. It was only the winter after their first sailing experience. The Barnes didn't hesitate. Midlife change didn't pass their lips. They were too busy, intensifying studies, dealing with shipwrights, overseeing repairs, borrowing money. But they made it, left their academic jobs, gained their tickets, and one day cast off lines and nudged the newly caulked, tarred, spit-and-polished, painted Stephen Tabor out of Camden harbor on a first cruise. That wouldn't have been unlike the one we joined, with two huge meals a day, prepared in the hold, eaten on the deck, with most passengers sitting on the planking, some on two large iceboxes. One was for food, the other for drinks passengers brought aboard. (A calamity for the martini bunch was when ice had to be rationed because of the warm weather). After breakfast, Capt. Barnes would leave one of the coves of Penobscot Bay, where we had anchored overnight, have passengers hoist sails, and head toward one of the inlets of crablike Acadia National Park. Everyone took a turn at the wheel. Mine to chidings from the skipper who asked me to look astern to the serpent path I had made. Life was lazy, supporting the "Albatross's" memory. There was never once strong winds, nor rain. Beer or coffee was passed around. Ellen Barnes took the occasional break from cooking beef for 26. The shrink (who needed one) fielded his overt passes. The captain or the mate would furnish collegial anecdotes about other windjammers off the beam, or embroider tales of island ghosts, or provide pictures of the hard life of Maine in winter. The apprentice would try to nap. About five o'clock each day, we found another cove, dropped anchor, prepared a boat to take us ashore after dinner. Years before we had camped with children in New England. Then, the water was so cold I pledged I would never again swim north of Cape Cod Bay. But aboard the Tabor we had a heat wave. It had reached 90F in Boston for a month. Just as well. It meant that M and I, each evening, could go in the sea. Like every passenger, with a bar of soap. This was before environmental concern, and necessary. There were no showers aboard. Nor lounge, bar, library, showtime. Our "cabin" was typical. It had a tiny copper water tank above a plastic basin on a shelf. Plus two wire coat hangers and two bunks designed for skeletons. That was luxury, Coming out of it one morning, I met the apprentice boy unfolding himself from a cupboard stacked with ropes, a hose, brooms - his sleeping space. Percy Rowe, a newspaperman for 50 years, served as reporter, foreign editor, news editor, assistant managing editor of metropolitan newspapers before becoming travel editor of the Toronto Telegram, then the Toronto Sun. He has traveled in 150 countries, every U.S. state and, of course, all Canadian provinces. He has had five non-fiction books published, two of them travel books. Percy Rowe resides in Toronto.

|

||||||

|

Register Free at travelteriffic.com Back to HOME PAGE Copyright © 2000 travelterrific inc. All rights reserved. Privacy Statement

|